Nick Cushing's Manchester City: Formation, tactics and style of play

A new series showcasing the tactical profiles of every Women's Super League team in partnership with The Underrated Scout

This piece is part of a special Team Profiles series with The Underrated Scout. Across the next few months we’ll be publishing pieces on the tactics, style of play and trends of every WSL team.

Share on social media and let us know what you think of the series.

After narrowly missing out on the title last season, Manchester City entered this current campaign determined to finally dethrone Chelsea. With the advantage of continuity—having made only minor adjustments and reinforcements to their squad from the end of the 2023-24 season—expectations were high. However, a strong start quickly gave way to struggles, as City dropped key points in direct clashes against Chelsea, Arsenal, and Manchester United, as well as against lower-ranked opponents like West Ham and Everton. Injuries undoubtedly played a significant role, particularly the defensive crisis and the absences of key players such as Lauren Hemp and Khadija ‘Bunny’ Shaw.

Their difficulties led new director of football Therese Sjögran to make a bold decision in March, parting ways with Gareth Taylor while the team sat fourth in the league and ahead of a League Cup final. Former manager Nick Cushing made a return as caretaker for the remainder of the season.

Now, we analyse City’s performances under Taylor and the tactical tweaks Cushing is introducing to get the team back on track, with the key objectives of securing a Champions League spot and making a strong push in cup competitions.

Attacking structure

Base formation

City operate in a symmetrical 4-3-3, with the striker tasked with stretching defences through deep runs or holding up play to allow ball progression. The undisputed starter in this role is Shaw, a complete forward who excels at executing these movements while combining them with a sharp goal-scoring instinct and a strong presence in the box, both in the air and on the ground. In her absence, Vivianne Miedema and Mary Fowler have stepped in effectively, highlighting City’s attacking depth. The wingers primarily serve as width-holding outlets, looking to take on defenders, reach the byline, and deliver crosses. As a result, City favour direct, athletic players with strong dribbling abilities and good final-ball execution.

Typically, this dynamic is maximised by deploying a left-footed player (Lauren Hemp) on the left and a right-footed one (Aoba Fujino or Fowler) on the right. However, they also have the freedom to cut inside, to add unpredictability. Attackers that are two-footed or that can invert well, like Kerolin and Fowler, are also particularly valuable. During Taylor’s time in charge, he regularly swapped the wingers mid-game, though this has become less necessary over time.

The midfield setup is one of City’s most distinctive features. While it consists of a traditional pivot and two central midfielders, the roles and player selection make it unique. Instead of a classic mix of a pivot, an attacking midfielder and a box-to-box midfielder, Taylor employed an aggressive ‘dual No. 10’ system, using two of Jill Roord, Jess Park, or Miedema. Only Roord has prior experience as a central midfielder, while the others are converted attackers. As a result, their focus is more on playmaking and box penetration than on traditional midfield duties.

Given the attacking nature of City’s midfielders, the team requires a high-level pivot—one capable of dictating tempo, managing possession, and progressing the ball. However, their role is just as crucial defensively, requiring tactical intelligence, proficiency in different types of duels, and the ability to defend large spaces, as this situation arises frequently. Yui Hasegawa embodies these qualities, making her a key figure in City's system.

The full-backs move in sync with the wingers, inverting when they stay wide and overlapping when they cut inside, ensuring all key attacking zones are occupied. The first approach is favoured, particularly on the left flank, as slightly narrower full-backs can provide additional midfield support.

Build up

In possession, City spread their centre-backs wide alongside the goalkeeper—who is required to be highly skilled with their feet—forming a diamond shape with the pivot. As the team's deep-lying playmaker and primary creative outlet, Hasegawa is often targeted by opposition pressing to disrupt City's progression. To counter this, she frequently makes lateral movements to free herself for a passing lane. However, in most cases, the first passing outlets for the goalkeeper and centre-backs are the full-backs, who naturally find themselves in more space and can carry the ball forward.

The central midfielders are less involved early on, as the aim is to have them receive later, on the move and facing goal. While this approach is effective, it can cause issues under intense pressing—seen in the home loss to Arsenal, where a more proactive presence from Roord in the early build-up might have prevented the early goal.

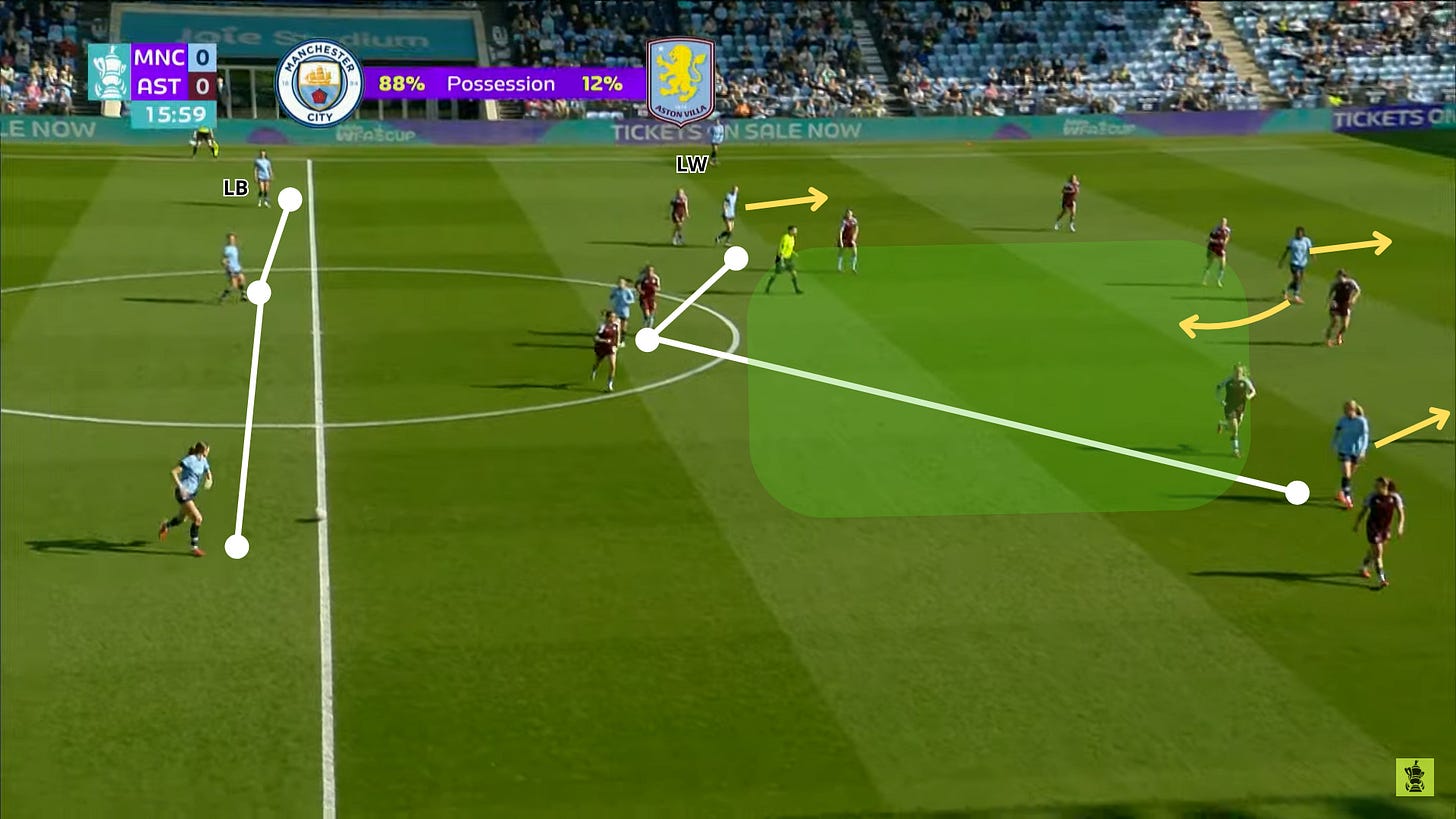

City progresses the ball primarily through wide combinations between the central midfielder, winger, and full-back, with the pivot occasionally supporting. While this phase follows the team’s tactical blueprint outlined in the team’s base formation, these players have the freedom to rotate positions. What matters most is not who occupies each space, but maintaining the right positioning and spacing to sustain these passing patterns.

Notably, the right-side positioning is perfectly complementary: the left attacking midfielder drops to combine, the right one pushes into the box, and the right-back tucks inside to reinforce the midfield, while the left-back overlaps. To balance this, the right winger holds width as the left winger moves inside. This system highlights City's structured yet fluid approach—players aren’t bound to rigid roles, but are expected to recognise and adapt to their teammates’ movements while maintaining positional balance on the pitch.

When building up closer to the opponent’s half, City often shifts to a 3+1 structure, where a full-back—usually the left one—tucks inside to form a temporary back three alongside the centre-backs and pivot. Meanwhile, the right-back pushes high, aligning with the left winger, effectively creating a 3-5-2 or 3-4-3 shape.

The central midfielders operate in the half-spaces, ready to combine with full-backs and wingers or make deep runs. The central area is left open to allow the striker to drop deep, triggering runs in behind from the midfielders.

The idea of emptying the central area is a key principle for City across multiple phases. In build-up, this can be taken to the extreme, with even the pivot shifting wide to allow a centre-back to push forward. While this may seem counterintuitive for a team playing with three midfielders, the goal is to maximise the impact of the dual No. 10s. By disrupting defensive references and using the striker’s drop to pull opposition lines out of shape, City create opportunities for the midfielders to make runs on the offside line or for the wingers to receive in isolation.

With a physically dominant forward like Shaw, City can also opt for a more direct approach, playing long balls from a defender or the pivot to the striker. Shaw excels in this role, not only due to her strength but also thanks to her explosive acceleration. She can break defensive lines even from a standstill, effectively dictating the pass in behind.

Defensive structure

General characteristics

In Cushing’s first game in charge, a 2-1 defeat to Chelsea in the League Cup final, defensive shape appeared to be one of his key tweaks, shifting from a 4-1-4-1 to a more conservative 4-4-1-1, at least when the team was level.

In this system, as the wingers drop into the midfield line, one central midfielder—usually Roord—pushes higher, vertically aligning with the striker. Her role is to screen the opponent’s deep-lying playmaker, while the other midfielder stays more in line with the pivot. City mainly mark man-to-man, especially in midfield, which can at times pull players out of position more easily.

This doesn’t rule out the possibility of Cushing reverting to a more aggressive 4-1-4-1 when City are chasing a goal or playing against weaker sides with defenders less comfortable in build-up. The trade-off would be leaving more space between the lines, covered only by the pivot. We will have to wait and see how this approach develops against different opponents.

On an individual level, the high work rate of the full-backs and wingers—along with the often-mentioned Hasegawa—is crucial, as they are the first to track back or cover for teammates stepping out. Additionally, given the attack-minded nature of the midfield, there is an inherent lack of solidity in that area—a conscious choice by the coaches. Neither Roord, Miedema, nor Park naturally prioritise defensive tracking or excel at ball-winning, despite the first two possessing a strong physical presence. While exceptional at indirect duels by cutting passing lanes, Hasegawa lacks the physicality to dominate direct tackles, though she always tries to compensate with determination.

Pressing

City employ an aggressive press regardless of the opponent, which is inevitable given the presence of five primarily attacking players. However, in extreme situations—whether chasing a result or protecting a narrow lead late in the game—this approach may be intensified or toned down.

In this phase, the wingers track the opposition full-backs, while one attacking midfielder joins the striker in pressing high, forming a temporary 4-2-3-1 shape and effectively engaging six players within a 20-meter area.

The press is directed outward, an unusual choice for a 4-3-3, as most systems with this setup aim to trap opponents inside to regain possession. It aligns with City’s aggressive system, where the "double 10" naturally leaves the midfield somewhat exposed. This is especially true when pressing at full intensity, where the 4-2-3-1 effectively shifts into a 4-1-5.

City’s intense pressing is particularly effective against teams using a 4-2-3-1, as the natural matchups favour a 4-3-3 when playing man-to-man. The pivot marks the attacking midfielder (and vice versa, as they often track each other throughout the match), while the central midfielders press the opposition’s double pivot, effectively keeping them out of the game. This was evident in the League Cup semi-final against Arsenal, where City dominated the midfield, further aided by Arsenal’s back-three buildup, which removed the left-back as an outlet.

In their chaotic 4-3 defeat to Arsenal in the WSL, City’s early deficit led to an overly desperate press, exposing its biggest risk—the large gap between defence and midfield. This issue is magnified at peak intensity or when pressing runs are mistimed.

If the opposition's attacking midfielder drops deep and the pivot follows, it creates a dangerous space behind them, easily exploitable by a direct team. Better support from the opposite winger or midfielder could help mitigate this vulnerability.

Transitional play

In offensive transitions, City remain a constant threat. With a complete striker like Shaw—who can outpace any defender both on and off the ball—alongside two fast, skilful wingers and two dangerous box-crashing midfielders, they always have five players ready to turn defence into attack instantly.

Defensive transitions, however, present certain challenges, as they expose two key vulnerabilities. The first stems from their man-to-man pressing up front, which naturally extends to the back, leaving gaps in midfield. Given City’s aggressive setup in that area, opponents can often find space to receive and drive at the centre-backs in one-on-one situations.

The second issue arises from the decision to invert the full-backs, which becomes especially evident when both execute this movement. While they compress the midfield, they also leave significant gaps behind them and beside the centre-back. These spaces can then be exploited by the opposition's wingers.

To address these weaknesses, City employ immediate and aggressive counter-pressing, especially targeting the ball carrier, aiming to either prevent or at least delay passes into those vulnerable areas. However, this tactic is situational and not always successful, as the space left exposed in that zone is somewhat systematic. As a result, the centre-backs and full-backs are the most exposed players during this phase.

Conclusions

Manchester City have demonstrated their potential to compete with Europe’s elite, thanks to a blend of fast-paced attacking play, a well-drilled tactical setup and excellent technical abilities. However, their season has been far from ideal. After a League Cup final loss in Cushing’s first match at the helm and with the league title now out of reach, the team’s focus shifts to their Champions League quarter-final and a critical FA Cup semi-final against Manchester United. Securing a trophy and third-place finish in the league, to guarantee Champions League qualification for next year, would help salvage the season, preventing it from being viewed as a complete failure.

Looking forward, much will depend on the appointment of a permanent manager, as there is no clear frontrunner at present. With that uncertainty, it’s difficult to predict how the tactical approach will evolve. If they can maintain the intensity and fluidity seen under Taylor while addressing weaknesses in transition and midfield solidity, City will remain a strong contender for both domestic and European titles in the future.